The Final Empire: Vol. 2 - PT. 3 ON THE WATERSHED

Chapter 19: THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE WATERSHED OF THE SAN FRANCISCO RIVER p. 319

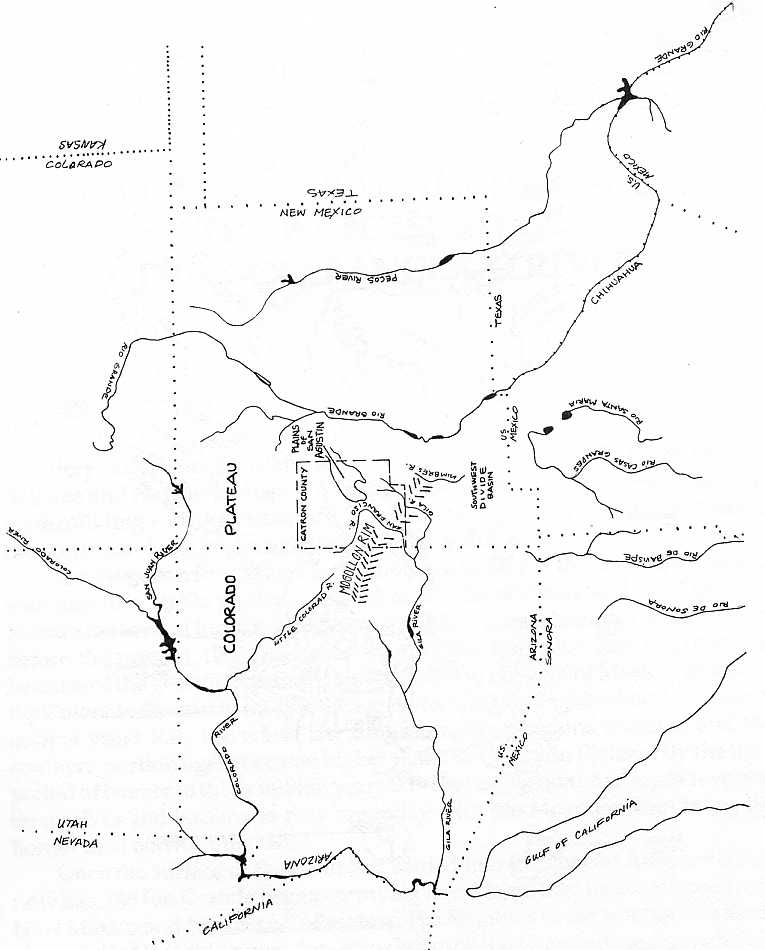

Very early in time, shallow seas covered the Southern part of New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico. As the tension of the North American tectonic plate colliding with the East Pacific Rise increased, the surface of the land across the American West began to crumple, shift, and rise.

The Mogollon Rim, which is the southern border of the Colorado Plateau, was part of a stable platform related to the Great Plains and the Colorado Plateau for several hundred million years. More than a hundred million years before the present, (B.P.), the area south of the Mogollon Rim began to fall because of the geosyncline that runs southeast to the Gulf of Mexico, elevating the Colorado Plateau to the North. Somewhere in the neighborhood of seventy million years B.P., the era of late dinosaurs, the positions reversed and the southern portion again became higher than the Colorado Plateau. By the time period of twenty to thirty million years B.P. the two sections had again reversed themselves and became as they are today with the Mogollon Rim being the border area between the two.1

Once the surface of the earth had settled into the general contours that it now has, the Rio Grande began emptying into a large lake located in Southern New Mexico and Northern Chihuahua. The Mimbres River and the Gila River also emptied into this sump. Sometime later the Rio Grande found the outlet in the gap between the mountains where El Paso is today and began to flow to the sea at the Gulf of Mexico. The Gila found another route out through Southern Arizona to meet the Colorado at Yuma. This left the Rio Mimbres to continue to run into the sump that has been called the Southwest Divide Basin, a basin 124 miles wide from which no water exits to either ocean.2

The great ice sheets of the last glacial period extended not much farther south than Santa Fe, New Mexico and as they receded the climate changed. As the ice sheet receded and after it was gone, the desert ecosystem progressed eastward and northward out of what is now the Sonoran desert. The montane system made up of pines, spruce and fir receded ahead of the piñon-juniper regime, which was followed by the desert regime.

Twenty-two thousand years ago the San Francisco watershed was probably entirely covered by forest of the pine-spruce-fir variety. As the desert regime expanded, the piñon-juniper zone began to move up in elevation. As the piñon-juniper zone began to move up in elevation and northward, grass lands followed behind and ahead of the present desert system. Grasslands dominated the northern Sonora-Chihuahua deserts for several thousand years before the present desert and the higher piñon-juniper zones were set around eight thousand years B.P.

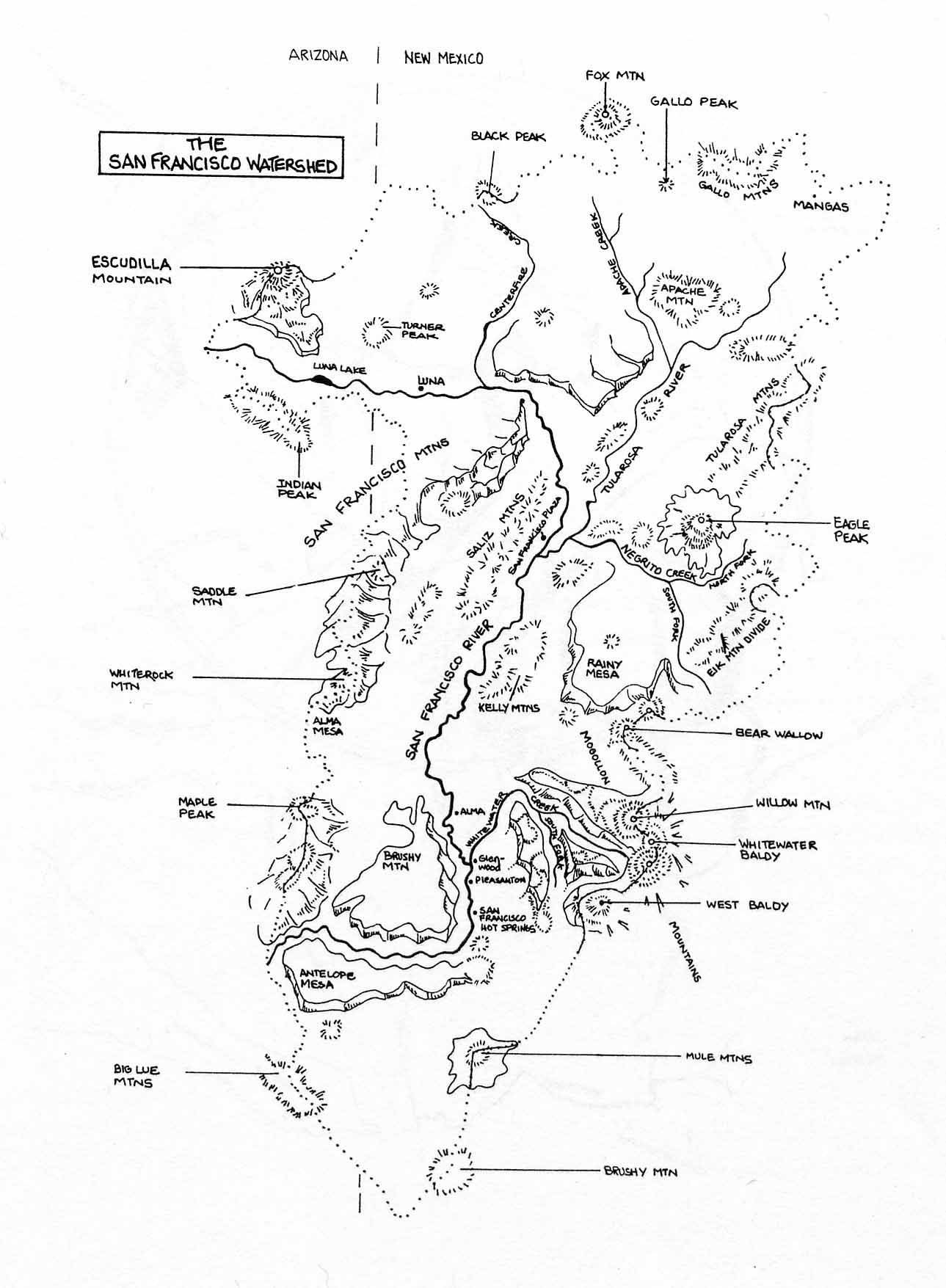

The Elevational Life Zones

The watershed of the San Francisco River is a unique region where within a distance of roughly 20 miles one can travel from the Sonoran-Chihauhuan desert type eco-system to an alpine ecosystem or life zone characteristic of Northern Canada. This is possible because the Rim rises out of the desert with peaks that are almost 11,000 feet in elevation. The life zones of the semi-arid desert in the Southwestern U.S., like other areas, are conditioned by elevation. As one goes up elevation, the temperature and moisture regimes become cooler and more moist. Because of this the same effect will occur if one goes long distances northward. Travelling north thousands of miles, one will cross the same life zones that one crosses by going up elevation along the Mogollon Rim. This abundance of life zones creates a fertile place for forager peoples because of the seasonal variety of foods available and also because it allows humans to avoid the effects of summer heat in the desert and the winter cold in the high mountains.

The lowest elevation of the San Francisco watershed is in the Chihuahuan Desert. The Mogollon Rim is the northern boundary of both the Sonoran Desert life zone and the Chihuahuan desert to the east of it. Phoenix, Arizona is in the Sonoran and El Paso, Texas/Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, being in the Chihuahuan. Though both are deserts, there are significant qualitative differences between them. The big differences are that the Chihuahuan is generally higher in elevation and the Sonoran has more species diversity. From the spot that the San Francisco river joins the Gila near the border of New Mexico/Arizona, back up toward the rim, is area that is transitional. It is the intermingling at the edge of two biogeographical regions. These are the Chihuahuan Desert to the south and the Colorado Plateau to the north. Even though the bottom of the watershed is in the Chihuahuan Desert and has those characteristics, these larger mega-zones both condition it.

The piñon-juniper life zone begins at roughly 5,000 feet elevation. This life zone predominates in the identifying tree species, smaller nopal cactus, and some grass species, bushes, as well as some forbs peculiar to this zone.

At the upper border of the piñon-juniper life zone is the ecotone called chaparral. Ecotone is the word that describes the intermingling of two life zones at their borders. This is a very rich ecological area that also contains oaks and manzanita as prevalent species along with the ponderosa pine which is the life-zone above it. The chaparral it should be emphasized, like other ecological specifics, does not occur at all places of the ecotone. Only where sun, soil and moisture are right will these large areas of chaparral appear.

At roughly seven thousand feet elevation the ponderosa pine forest begins. This is the zone of the cool summers and quiet nights. Between 8,500 and 9,000 feet that life zone begins to shade into the fir-aspen zone. This is the high elevation of snow, springs, abundant fungi, boggy meadows and the beautiful aspen forests of autumn.

Above this zone is the spruce-aspen zone. This zone is everything that one would find in a northern Canadian forest. Above this zone at roughly 10,500 feet elevation we find the tree line and then hardy grasses and shrubs above at the top of Mogollon Baldy and Whitewater Baldy, the same type of areas of moss, grass and low bushes that one sees in the arctic. Each of these life zones is a general approximation as to elevation, and vegetation cover. The zones vary; for example, a warm, drier, south facing slope would have characteristics of a lower elevation than a north slope which is colder and on which the moisture evaporation is not as great. There will be areas also that are in the rainshadow of high ranges and so receive more moisture than would the same face in an area that was not in a rainshadow. Narrow canyons, especially on a north face can vary the life zone considerably. Soils also have an effect on these zones. Often if soil is poor a zone will reflect species that are characteristic of the next zone lower. Generally speaking, the life zones do maintain the given elevations with the proviso that the farther south one goes, the higher is the elevation of each life zone.

Though certain species are identified with particular life zones, it should be kept in mind that there are seasonal migrations of birds and animals and that also plant species will migrate into any area to their liking. A good example is the ponderosa pine which has its own life zone but in the days before the empire when they were not felled, they would flow down the moist canyons and stretch along the live streams at lower elevations far out into the desert as long as their roots could reach water. The elk who now live cloistered in high mountains everywhere, are naturally more of a plains and meadow animal (they are predominantly grass grazers, rather than browsers). Since the coming of empire they too have retreated.

The Moisture

Generally, precipitation on the Watershed increases about four inches for each one thousand foot rise in elevation, but there are exceptions that modify this rule. The watershed receives weather from both the Atlantic (Gulf of Mexico) and the Pacific in seasonal alternation:

"Winter is the driest season because much of the moisture from Pacific Ocean storms moving inland is removed over the mountains to the west. The seasonal difference is less pronounced west of the Continental Divide than to the east. The main source of moisture in the summer is the Gulf of Mexico. Moist air enters New Mexico in the general circulation from the southeast about the westward displaced Bermuda high pressure area. Two-thirds of the annual precipitation falls during the warmer six months, and half the annual average precipitation falls from July through September. This is mostly from brief, but often heavy, thunderstorms."3

Even though the low end of the watershed should follow the altitudinal pattern for rainfall it is nearer the air flow of the Atlantic out of the Gulf of Mexico which brings it more moisture. Also rain clouds headed north sometimes back up against the escarpment of the Mogollon Rim which is thousands of feet high. This also helps cause rain.

The two phase, winter-summer alternation of moisture is significant. The effects of this can be seen particularly among the grasses and the forbs, which are plants that are smaller than bushes but that are not grass or grasslike. The dual wet periods bring on cool season plants that achieve their growth during the winter rainy season and warm season plants that are adapted to the summer rainy season. The bulk of the plant species are warm season. Nonetheless, the life of cool season plants assist in feeding the browsers and grass eaters during the cold winter months and forbs such as filaree and the cool season perennial grasses help cover the exposed soil when other plants have died back because of the cold.

The summer thunderstorms not only bring in moisture but there exists a complex relationship between the organic life of the area and the moisture-electrical nature of the earth and of the upper atmospheric layers. In controlled tests it has been discovered that plants in the desert will grow significantly faster if they have natural rain from thunder storms than from the same amount of water from irrigation. When weather systems move about the planet, they carry their own electrical natures. The stories are well known of people with arthritis or old injuries who can predict the weather several days in advance because of pains. According to the study, The Ion Effect: How Air Electricity Rules Your Life and Health, by Fred Soyka and Alan Edmonds (Bantam, 1977) the "devil winds," the dry, hot winds like the Santana in Southern California, the Sharav in Israel and other such winds around the globe, show that the positive ionization that causes the feelings in the bones, arrives several days before the winds and weather fronts arrive.

The earth at the surface is more predominant in negative ionization than the upper atmosphere which predominates in positive ionization. Negative ionization, laboratory tests with plants show, is very life enhancing and oppositely, environments that predominate in positive ionization can actually make plants wilt as well as making people ill and irritable, because of its effect of triggering the adrenal glands which after prolonged elevation throws humans into depressions and anxieties because of the upset of the hormonal balance and blood sugar levels.

When a thunderstorm comes through the region, lightning equalizes the positive and negative charges of earth and atmosphere. As the thunder storm begins with its increase of negative ionization on the surface of the earth, most people experience an euphoric feeling, as they do in showers or when sitting near waterfalls or seashores (aerating water is one producer of negative ionization). This is caused by the heavy negative ionization amassing just before this tremendous energy exchange between the upper atmosphere and the earth - the lightning. In sum, the watershed of the San Francisco river is connected to the whole earth through these and many other macro-events.

Life Before Empire

Prior to the invasion of empire, palmate antlered Merriam elk grazed out on the lowland flats and up into the edges of the ponderosa. Mule deer too would be seen far out on the flats as well as the predominant animal of the grasslands, the pronghorn. The pronghorns were the most abundant on the grassland flats, their herds often numbering in the tens of thousands. The open grasslands, which were much more in evidence then because of grass fires, supported other animals such as the coyote and the wolf, which followed the herds.

Prairie dog towns were numerous and each contained hundreds if not thousands of the small animals. These burrowing rodents numbered in the millions in the area and provided a subsistence base for the coyote, wolf, raptors and the black footed ferret as well as the human occupants of the area, who found them especially easy to catch during summer downpours when the prairie dogs would drown out in their burrows and come to the surface of the ground where they were easily caught. The drowning of their burrows helped the earth accept and hold the sudden downpours of water and deterred sudden runoff.

The riparian habitat along the streams, the most fertile life of the desert, was originally much different. The cottonwoods were very few because they made such good food and construction materials for the beaver, but there were more willows and other trees. The beavers stretched from the Colorado River at Yuma, Arizona, up the Gila, then in all of its tributaries to the tops of the watersheds. Partly because of their activities, the water ran slow and the pools were many. The cienigas (marshes) that they created became home for many animals, water birds and waterfowl and the abandoned beaver ponds eventually dried and became beaver meadows. The beavers also created environments for other human food such as the tules (cattails), the arrow leaf potatoes and all of the animal life that visited that oasis.

The riparian habitats were the real fertility generators. These streams, such as the San Francisco, carried life out into the desert and enabled life to migrate upstream. The ponderosa were found in the canyons and valleys many miles down out in the desert as were the bears, especially grizzly.

Dr. John P. Hubbard, formerly of the Rockbridge Alum Springs Biological Laboratory and now Supervisor of the Endangered Species Program of the New Mexico Department of Fish and Game describes this ribbon of verdant green that drains the Watershed:

"Biologically, the San Francisco Valley, may be likened to an arm of the sea penetrating the midlands and highlands of southwestern New Mexico as a corridor from the lowlands to the west. The ‘ocean’ which it represents is the extensive, sub-tropical region of the southern Arizona and adjacent Mexico, which may be termed the plant and animal province of the Sonoran Desert, or simply the Sonoran biota. It is mainly along the San Francisco River and it’s sister stream, the Gila, that the Sonoran biota penetrates southwestern New Mexico and between the two valleys an impressive representation of such plants and animals is found. Among plants included are such dominant species as the Fremont Cottonwood, Arizona Sycamore and Arizona Walnut, while some examples among the fauna include most of the native fish, the Gila Monster, Arizona Coral Snake, Arizona Cardinal, Albert’s Towhee and the very rare Coati-Mundi. Not all of these have been found in the San Francisco Valley, but studies there are far from comprehensive and all may well occur, along with other Sonoran forms.

The San Francisco and other such valleys are also what might be thought of as oases for plants and animals which require permanent surface water or for the habitats that it fosters. Besides fish, animals needing an aquatic environment include many amphibians, turtles, water birds and such mammals as the beaver. Some of these and many other species require the riverside woodland and other habitats that the valleys sustain. The differing availability of surface water from the floor and up the slopes of the valleys results in a great diversity of habitats within a relatively small area. Such habitats range from stands of broadleaf trees and marshes to grassland and desert-like growths of mesquite, yucca and cacti. This large array of habitats in turn produces a diversity of animal life, so that valleys such as the San Francisco and Gila sustain a great many kinds of organisms. For example, in the Gila Valley some 115 species of birds breed, which is almost a fifth of the species regularly breeding in North America north of Mexico, and the as-yet-incompletely-surveyed San Francisco Valley will probably prove to be nearly as rich. The diversity of birdlife and doubtlessly of other groups of organisms in the vicinity of these two valleys is greater yet when one considers the very large array of habitats existing from the valley floors to the peaks of the Mogollon Mountains directly to the east. For example, within a 25 mile radius of Glenwood almost 200 species of birds may be expected to breed, a figure equalled or exceeded by few nonmarine regions in temperate North America.

The San Francisco Valley seen from afar, is a narrow ribbon of verdure through the usually brown hills and plateaus of southern Catron County, but in places it has been changed by settlement and agriculture. The open woodland along the river is predominantly cottonwood and willows, with other, less numerous trees including box elder, ash, walnut, sycamore, hackberry, oak, desert willow and others. Interposes between this riparian woodland and the river is often a fringe of the evergreen, shrubby composite called batamote or seepwillow. Beyond riparian woodland on the floodplain are thickets of mesquite and catclaw and these give way to chaparral and an evergreen woodland of oaks and junipers on the slopes.

Canyons opening into the San Francisco Valley are numerous and frequently support interesting and different assemblages of plants of their own. For example, in Whitewater Canyon are Arizona Alders, Netleaf Oaks, and Narrowleaf Cottonwoods - plants typical of the foothills rather than of the low Sonoran valleys. Towering over the San Francisco Valley are the Mogollon Mountains, which support pine, fir and spruce forests. All of these habitats combine with plains, cactus flats and others to provide the great biological diversity in the region centering on the San Francisco Valley, truly a natural treasure."

The Fire Regime

Another macro-dynamic of the watershed was fire, a cyclical occurrence with the grasslands before they were grazed down by cows. They burned often when set by lightning in the fall when the tall grass was dry. The fires helped the grassland maintain itself by burning back the other types of plants that would like to live there themselves, such as the cactuses, the larger forbs, the juniper and the piñon. High in the mountains, forest fires still become wide-spread in July. One period between the two-phase rainfall regime, the months of April, May and June, are quite dry. As this annual mini-drought continues into the summer, everything becomes desiccated and the humidity drops very low. Toward the first of July the dry electricity in the air begins to crackle and thunderheads begin to appear. Small at first, these thunderheads grow and finally the shock of thunder is heard, first in the highest mountains. Through the coming days as the dryness crackles and the thunderheads become larger, the fires begin. It seems that until it primes itself sufficiently, the thunderhead tribe cannot drop any rain and so the first lightning storms come through and there is lightning but no rain to put out the fires that are caused. Each July the Mogollon Rim has the highest fire rate of anywhere on the continent.

It is usually a week or ten days before the system can get itself primed and finally begin to drop rain. As the high mountains begin to get drenched, the phenomenon begins to generalize into the lower altitudes. Finally the immense flats stretching out toward Mexico are receiving a little rain. As the rain begins, the fires decrease sharply in number but continue sporadically until fall when the lightning storms cease. The view of a native, undisturbed ponderosa stand is the view of a park. From a grassy meadow one can look into the forest for a long distance past the giant, "yellow belly" ponderosas. Ordinarily, the fires that come through are ground fires that move along the ground rather slowly and ignite a bush here and there or a patch of bunch grass. The fire may singe, but never burn down the ponderosa, whose branches don’t begin until fifty feet up. The effect of the fire is to open the forest and to prevent the ponderosa from entirely taking over so that a variety of other life can have space also. This is especially true in brushy chaparral where the fires are a common and natural occurrence. Fires actually help the fire-adapted varieties of that fertile zone.

The fires also help the aspen which can be forced out by the stronger fir and spruce at that higher zone. In a sense the aspen are nurse trees that come into an area first after disruption, along with the bushes with berries and other high elevation forbs and grasses. In a burned over area the aspen will resprout and hold the soil, help cool the area and help keep it moist until the evergreens can regenerate themselves.

The Human History

Humans were present at least 13,000 years ago in the southwest as indicated by the "Folsom Man" archeological find. Along with these humans were giant ground sloths, the dire wolf, the short faced bear, the saber-toothed cat, the mastodon, the mammoth, the giant peccary, camels, pronghorns of two additional species other than the one that exists today, ancient bison, the forest ox, the mountain goat, the tapir and several species of early horses. Like the large mammals world-wide, these species have disappeared during the last 10,000 years as the climate changed from grasslands in the lower areas and flatter areas of New Mexico to a more piñon-juniper regime.4

It is difficult to say how long humans have been in the Southwestern U.S. Most Native American people say that they have always been here. The academics cling to the Bering Strait Migration orthodoxy.

In the Mogollon Rim country we know that humans managed their longevity partially by corn. Although there were no doubt humans in the area earlier, small corn cobs have been found that date back 5,000 years. The archeological work at Bat Cave and Tularosa Cave, on the Watershed, show that corn came into the area at least that early and beans followed several thousand years later. Because some remains survive from 2,500 years B.P., we know that humans were then living in pit houses in the area. There is evidence of pit house people receding back many hundreds of years earlier in what is called the "Cochise Phase" in the Southwest, but no sites of that nature have been excavated on the San Francisco watershed.

On the San Francisco watershed there has been one major excavation of a 2,500 year old pit house village, which is called the SU site (after the large ranch with the SU brand). This site contains eighteen dwellings and it is considered by the principal archaeologist to be the only one within a fifteen to twenty-mile radius.

The archeologist, Paul Martin, describes the dwellings:

"Mogollon houses of the Pine Lawn phase lacked antechambers, partition walls, slab-linings or firepits. Furthermore, the roofs of early Mogollon houses were not supported in any standard fashion, as were the Anasazi roofs. Instead, one finds anywhere from one to six primary roof supports set apparently in higgledy-piggledy fashion (except the single roof support, which was placed near the center of the house) and never twice in the same way. Early Mogollon houses are irregular in shape, resembling an amoeba and are very shallow. Lateral entrances to Mogollon houses are not always present but when these entryways are found they may be short and stubby, or long with upward-sloping floors, and are oriented toward the east. Deep pits, sometimes several to a house, are frequently found in Mogollon houses."5

Most of the Pit House remains on the San Francisco watershed have been found in the chaparral area. The chaparral and the riparian habitats along the live (year around) streams must be considered the real fertility generating "islands" of the watershed. That we find the pit houses in this zone should be no surprise. From the chaparral zone the pit house people had the ecological zones above and below them available for forage. There is no doubt that the pit house people were sure to be in the chaparral in the fall when the natural harvest comes in. When the acorns drop in the fall and the piñon nuts are ready, the service berry, sumac, manzanita and rose hips ripen. Yucca bananas can also be found in the chaparral as can the smaller agaves. When the harvest is ready in the chaparral, the life of the area comes in to eat. Deer, bear, peccary, turkey, squirrels, pack rats, jay birds and others feast on the bounty. These animals attract others, coyotes, wolves, bobcats and mountain lions, who eat the herbivores.

Transition to Sedentariness: The Kiva People

Food sources of the Pit House people as shown by excavations over a wide multi-state area differed according to the area and its availabilities. Subsistence shaded from almost pure hunting and foraging to almost exclusive farming. Anthropologist David Stuart gives some clues about the relative value of nomadic versus sedentary lifestyles. He says:

"It took field work among remnants of the world’s nomadic peoples and in remote agricultural villages to discover the reasons. Under conditions of very low population density, nomadic hunter-gatherers earn a living with only 500 per capita hours of labor each year-and malnutrition is surprisingly rare! Unsophisticated agriculturalists required more than 1,000 per capita hours annually to do the same-but malnutrition and infant death are more common. So are crop failures."6

"Work time" stands at near 2,000 hours a year for the average industrial worker.

Beginning in 500 A.D., the San Francisco watershed was populated by the Kiva People (popularly known as "the Anasazi"), who, through change from the Pit House people or introduction of another strain of humans, were living in above ground "Pueblo" style buildings and all conducting spiritual activities in underground Kivas. These people are estimated to have remained on the Watershed until 1250 or 1300 A.D. They were closely related to the Mimbres subgroup nearby, one hundred miles to the east, as shown by the large number of "Mimbres style" pots dug up on the Watershed of the San Francisco.

One can hardly walk around on the Watershed at the chaparral level or below, on any suitable housing site, without finding pot shards, stone tools, arrow heads or other remains of the Kiva People. Archaeologists estimate at least 30,000 people lived in the area before the disappearance. Archeologist Christopher Nightingale who has done the most extensive survey of the area puts the figure at a level, "In excess of 30,000." No more sharp contrast could be drawn in cultural land use patterns than the fact that 2,700 people live in the same area now and only marginally, within the definitions of the industrial society.

The culture of the Kiva people was no doubt very similar to the nineteen native pueblos in New Mexico today. The adaptation to the land was by village. The village was located generally near live water so that water could be channelled in to the crops. The basic subsistence crops were mother corn and her daughters beans and squash. Beans and corn provide a complete amino-acid combination. Particularly, in the New Mexico region, green chiles were also a part of the inventory. There was tremendous variation within each of these species. The strains of corn held even today by contemporary pueblos vary according to color, water needs, temperature needs and other considerations. This same situation applies also to the bean and squash varieties.

There probably were also ancillary cultivars, such as there are in the pueblos today. Domesticated types of the wild groundcherry are grown, sunflowers are often seeded around fields, devil’s claw is often domesticated and grown as well as many other useful plants. It should be mentioned that various "weed" species are usually kept around the field areas for various purposes also.

Pollen analysis of archaeological digs in Central America indicate that for nine thousand years the Mayan adaptation diet has predominated in corn, cucurbit (squash), beans, meat, agave, chili peppers, ceiba (a tree fruit), bristle grass (setaria-seeds ground to flour), cactus and amaranth.

Mother corn and her daughters are the Meso-American adaptation. In reality, the Anazasi were suburbs of the centers such as Copán and Tikal of the Central American Mayas. The pueblo cosmology, especially the Hopi, shares major patterns with the Meso-American. In Frank Waters’s definitive work, Mexico Mystique: The Coming Sixth World of Consciousness, (Swallow Press, 1975), the similarities are clearly laid out. In the pueblos today the traditional shell necklaces called heishi are made of shell from both the Atlantic and the Pacific. The old trade routes that connected the oceans, Central America and the pueblos to the north are known. In some Kiva ceremonies, parrot feathers are still required. Just below the center of modern nuclear war at the city of Los Alamos, New Mexico, is the ruin of an ancient pueblo. As one walks up the trail approaching the mesa where the ruin is located, a long serpent is visible on the cliff face. It is the symbol of Quetzal Coatl, the redeemer and symbol of the life force of Meso-America.

From diet flows social structure in natural culture and then in the industrial inversion, diet becomes the result of what plants mass machine production methods can most profitably grow and harvest. Because of mother corn and her daughters, the pueblos must stay in one place, thus houses. The irrigated varieties of these plants require flat land near live streams. This means that some authority must apportion the scarce water and land resources. This all results in something of a stratification in the pueblos but this is not the hierarchy of the empire with which we are familiar. In most pueblos today there is no permanent leader. Leadership is rotated annually in a complex formula the precludes complete elitism. Rotation of responsibility among other "offices" and even rotation of different groups is customary. The cultures of the pueblos, which are each self-governing entities, are extremely complex. It is this complexity in addition to the cultural values that mitigates the solidification of exploiting elites.

Often in the pueblos there is an equal division into two parts, that anthropologists call moieties. One is born into their moiety. In several pueblos these are called the summer people and the winter people. This carries with it certain ceremonial obligations that relate to the seasons as well as others. One is born into a clan such as turtle, eagle, or bear. One is often born into one of several divisions in the moieties. One often joins a secret spiritual society that may or may not be related to one’s birth line. One then, may marry. This will double the relational web of one’s life. Finally, as an individual, one will become distinguished for talents or style and that will produce its own conditioning of all relationships. Though this listing may seem long, it by no means is exhaustive of the tremendous complexity with which the pueblos function. We must add to this a calender cycle that includes both functional acts such as ditch cleaning, the first deer hunt, the time of bean planting and such. The other important calendar cycle is the ceremonial cycle which is winter to winter and includes many ceremonies large and small, public and private.

One of the big reasons that jobs in industrial society destroy pueblo culture is that the functioning of this great swirling, ever-changing mandala of culture requires- time. In this mandala, all is integrated, the cosmos- through the star movement timing of certain ceremonies, right down to the seasonal bean dance. It is this constant flux of responsibility and the dense web of human relationships that have prevented any pueblo culture in known history from being taken over and eradicated in any permanent way.7

This is the culture that typified the Kiva People of the San Francisco watershed. The Kiva People of the San Francisco left at about the same time as the other "Anazasi" in the southwest, from 1200 to 1250 A.D. Some questions remain. Why did they leave? Did they exhaust the soils? Did they deforest they area for firewood during their long tenure? Did they deplete the animals and wild foraging plants to the point they have no supplemental food sources? We don’t know, we can only speculate. Their disappearance could have been something entirely social, following a vision or prophecy.

True Forager/Hunters: The Apache

The forager/hunter people commonly known as the Apache came into the watershed soon after the exit of the Kiva People. The groups popularly known as Apache are Athabascan. They are part of a sizable language group that includes the large Athabascan tribe of northern Canada, the Navajo, the Hoopa on the coast of northern California and the decimated group who lived near Grants Pass in southwestern Oregon.

Just as the G/wi, living in one part of the Kalahari Desert used tsama melons as the basis of their food sustenance, the !Kung living in another part of the same desert used the ground nut, mongongo, for their primary subsistence. In the same way the various Athabascan tribes of the Southwestern U.S. maintained different lifestyles based upon the different ecologies that they were integrated with, stretching from the Great Plains in the vicinity of Oklahoma and Northern Texas (Kiowa and Lipan Apache), through Northeastern New Mexico (Jicarilla), to Eastern-Southeastern New Mexico (Mescalero), then across the Mogollon Rim and into Central Arizona (Hot Springs, Chiricauhua and Western Apache). One band, the Nednhi lived in the northern part of the Sierra Madre in Mexico. Each of these groups and areas maintained a life style based on the particular life system with which they lived.

It was the northern branch of the Chokonen (Chiricahua Apache) that specifically occupied the San Francisco watershed. This band was led by Chihuahua in the last days. This is the northern division of the Chokonen and the southern band was led by Cochise. Though we say that a band is specifically identified with an area, it may be more accurate to say that they were localized there. Bands ebbed and flowed and often entered each others customary area to visit and forage. On the east of the Watershed along the Mogollon Rim and on its back side, to the north, lived the Bedonkohes. These people are popularly identified by their famous son by marriage (he was actually born into the Nednhi Apaches of the Sierra Madre) Geronimo. Just to the northeast of the Bedonkohes, along the Black Range and north on the west side of the Rio Grande to the vicinity of what is now Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, lived the Chihinnes- Hot Springs Apaches, popularly identified with the last free leader, Victorio.

The bands were identified with these areas, though they ranged widely. In the last days of the resistance it is known that they ranged from southern Colorado to south central Mexico. Mobility was the key element in their ecological adaptation. They harvested the surpluses of the land and they had to know where these would be and when. The ethnobotanists, Morris E. Opler and Edward F. Castetter give this summation of the Apache forager lifestyle and it certainly could be applied to all of the forager people, in general, that have lived on the earth:

The Apache; "Moved with the seasonal change of weather and followed the wild food harvests as they occurred.... When colder weather came he (sic) removed to a lower altitude; in summer he (sic) was in the highlands again. When the mesquite and screwbean ripened on the flats, parties of Apache were there to gather them; when the hawthorn hips were ready in the highlands, Apache were nearby to take them. These people knew nature’s calendar by heart, and no matter whether a grass seed ripened or a certain animal’s fur or flesh was at its best at a particular time, the Apache was present to share in the harvest."8

The integration of the forager people with the life of the earth is essential and natural, so that the weather, the daily habits of the animals and plants and one’s own intuition vis-a-vis the natural world make up a composite of perception in which one becomes part of the life of earth- becomes natural life.

James Kaywaykla was a grandson of Nana. Nana was the elder who rode with Geronimo. Kaywaykla was a Chihinne. The tribal name of Chihinne means Red People, referring to the red band of clay that the tribespeople put across their faces just under the eyes to cut the glare of the sun. (In modern day usage they are called the Ojo Calientes or Hot Springs Apaches.) Kaywaykla tells of the foraging habits of his people. He says in translation:

"My people spent their summers in the mountains of New Mexico, carefree, untrammeled. They migrated to Mexico in the fall, living off the land as they went, killing game, harvesting fruit, and giving thanks to Ussen for the good things He had given. They knew the land of jungles and of tropical fruit. They knew the people whose land they crossed. They were on the very best of terms with Cochise and his band. They penetrated the fastness of Juh, Chief of the Nednhi, and were received as brothers. When they in turn came to us we gave freely of our best."9

Each mountain range was a repository for many of the items that the Apaches used. On the northern edge of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the stronghold of the Nednhi Apaches, lastly led by Juh, the high mountains and foothills provided agave (agave palmerii), deer, walnuts (juglana rupestris, var. major), acorns (quercus emoryii, q. reticulata, q. turbinella, q. grises, and q. arizonica), honey, nopal fruits (opuntia phaeacantha) and mesquite (prosopis juliaflora). The Chiracahua band, popularly identified with the leader Cochise, were centered around the Dragoon, Chiracahua, Peloncillo and Hatchet mountain ranges and they had similar food with the addition of datil yucca (yucca baccata), palmilla yucca (yucca elata) and sumac. Pronghorn (often called antelope but they are not antelope, they belong to a family that is neither deer nor antelope) were available on the flats separating the ranges. The Bedonkohes, Geronimo’s tribe, were centered on the headwaters of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers. This area provided mountain sheep, pronghorn, elk, deer, acorns, mescal (agave), datil yucca, nopal fruit, mesquite and piñon nuts. The Chihinnes, who centered around Ojo Caliente, enjoyed a variety similar to the Bedonkohes just south of them. These are primary items and dozens of other items of less importance were used.10

Probably the most important items of the Chokonen and Bedonkohe diet on the Watershed were the pronghorns, mesquite, mescal (also called agave), and acorns. The pronghorns existed from the desert area up to at least high ponderosa forest. More important than elevation is the pronghorns’ need of flat land. With their amazing speed of 50-70 mph and binocular vision it is necessary for them to live in flat areas at whatever elevation they can find them. The flats must be sufficiently expansive to allow them the distance to run from their pursuers and the flats also must be smooth topsoil without rocks. As these animals existed from the desert up to the higher regions, they were a favorite animal food of the native people.

The agave was probably the most important plant food of the Apache.11 The agave grows best in the desert region but will grow up into the piñon-juniper to the ponderosa, although the form of the plant found there is smaller. Anthropologist Winfred Buskirk says that the agave could be used at any season, although because the plants were abundant in an area that was the Apache’s wintering environment this was normally when they were used. Any of the plants would suffice, but the best were the ones that were preparing to flower. The agaves, which are sometimes called the "century plant," only bloom once and then die. The northern agaves may bloom at ten to fifteen years, but agaves farther south in Mexico may go as long as thirty years before they flower and die:

"In the fall and winter good edible plants could be selected by observing the leaf bases and the terminal shoot, a thickening of which indicated that the plant would bloom the following spring. The best time for gathering was in the early spring, usually in April, at which time some of the plants blossomed. At this season enough mescal was prepared to last through the summer or longer."12

The root was severed under the bulb and the plant taken out of the ground. The leaves of the plant were trimmed off and it was ready for roasting. The crowns average twenty pounds each and as many as forty would be roasted at one time. Basehart, who studied the Apache subsistence cycle, states that the Chiracahua gathered forty to sixty crowns per year per family, and that a month or more might be spent gathering the food.

The agaves were roasted in an earth pit, up to twelve feet in diameter and two to four feet deep. The pit was filled with oak and then fired. Small eight inch diameter lava rocks were layered over the coals, some beargrass put in as a cover and the agaves were then put into the pit. Beargrass was again put over the top and the pit was sealed with earth; an additional fire on the top of this earth appears to have been optional. Kaywaykla says that his people put the long narrow leaves of the agave down into the pit, standing them upright as they filled the pit. As the cooking progressed, they were able to check on the progress of the cooking by pulling out a leaf. The condition of the leaf indicated when the agave was cooked. Various references indicate that the agave was cooked from one to two days. After baking, the agave was pounded flat into sheets several inches thick and dried like jerky (sun dried meat). The food in this condition could be kept for a matter of years. A one-quarter cup serving of prepared agave provides thirty calories and more calcium than does a half glass of milk.13

Agave is very sweet and could be used with pemmican, mush, mixed with flour for breads or used in many other ways in addition to eating the dried material without further preparation.

Another use of the agave was for sewing. The sharp spine on the tip of the agave leaf can be used as a needle and the strong fibers of the leaf are used as a pre-attached thread. The leaves are simply dried and the pulp of the leaf pounded out so the remaining portion, the fibers, are used in braided or twisted fashion with its own sharp needle. Kaywaykla mentions that it is an effective method with which to sew rawhide soles onto moccasins. The juice of young agave leaves is also used medicinally when signs of impending scurvy are detected.

Both types of yuccas, (elata-narrow leaf and baccata-wide leaf) were used in the same life zone as the agave. Elata is the familiar soap yucca and its stem and flowers were also used as food. Baccata or datil yucca bears a fruit of exquisite taste which grow from five to seven inches long. These fruits are called yucca bananas and they can be eaten fresh, roasted, dried or ground into meal. The young inner shoots of this plant can also be used.

The nopal cactus is a prolific plant in the desert and up into the piñon-juniper zone where its varieties grow smaller. The elephant ear leaf can be eaten as well as the fruit which is called "prickly pear" or tuna, in Spanish. In Mexico and in Latin groceries in the U.S., the chopped leaf can be purchased as "nopalitos". The fruit of this plant was especially used by the Apaches.

Mountain sheep were abundant in the desert ranges and in the foothills of the Mogollon Rim. These animals gain security by their unusual agility in the rocky heights of steep hills, mountains and cliffs. While not necessarily bound by life zone, it occurs that this type of terrain exists primarily in the desert and piñon-juniper regions.

Like many of the animals, the Apaches migrated seasonally, but this did not mean that they moved en masse everywhere they went. Basehart says, "Not all... would move any great distance in a given year, nor would the same families and larger social units travel in identical directions and distances from year to year. Thus, a group might remain close to a central base throughout one year, and travel a considerable distance the next; alliances between families were not permanent, but could shift from season to season."14

The Apaches did much grinding of flours. Seeds are the obvious basis of flours but seed coatings, pollen and other plant parts can also be dried and ground as flour either by itself or mixed with other desirable flours. Sources of Apache flours were mesquite, screw bean mesquite, agave, acorn, piñon, sunflower seeds, walnuts, juniper berries, grass seeds of many types, chia in the lower elevations, devil’s claw seed, coyote melon seed (calabazia), tule pollen, and amaranth seeds.

Prominent among the greens used was the amaranth (amaranthus palmeri). (Gary Nabhan says of the plant; "The raw Amaranthus palmeri greens [one hundred grams] contain nearly three times as many calories [36], eighteen times the amount of vitamin A [6100 international units], thirteen times the amount of vitamin C [80 milligrams], twenty times the amount of calcium [411 mg.], and almost seven times the amount of iron [3.4 mg.] as one hundred grams of lettuce.")15 The immature rocky mountain bee plant (cleome serrulata) was also a staple green. Other plants known to be favored by the Apache were wild potatoes (solanum jamesii) and wild onions (allium cernuum), both which grow prominently in the chaparral.

The Apaches did some planting in the canyons and river bottoms. The detailed knowledge of the different corn colors and strains shown by anthropologists' informants, demonstrate the fact that there must have been considerable farming. The crops raised were essentially corn and beans but, of course, the seeds of wild food plants were often scattered around camp so there would be an abundant supply near.

Anthropologists estimate that the Apaches used nearly fifty species of food plants comprising 40-50 per cent of their diet. Because anthropologists were visiting the Apaches long after they had been concentrated in the reservation camps and long after the methodical and planned destruction of their culture had begun, it would be difficult to inventory their complete knowledge and lifestyle. We could suffice it to say that the Apaches probably made use of everything that was reasonably edible and used a large inventory of what they found on the land for materials to create the shelters, tools and the basic necessities of their life.

Humans of course do not live in a vacuum of simply eating. The Apache display of humility and sophisticated ethical cultural perception of much of the rest of the Pleistocene inheritance. Kaywaykla, for example, speaks of the consideration for the animals and other life of the earth. He points out that animals were never killed at waterholes because of the consideration that all beings were put on the earth and that they must drink, too. They were not killed there out of fairness to them.

The Arrival of Empire: The Story of the Last Native People on the Watershed

Santa Fe, the Capital of what originally was called the Kingdom of New Mexico, was already a thriving village when the Pilgrims reached Plymouth Rock. Spanish immigrants, many of them from northern Spain, reached New Mexico by the Fifteen Hundreds. They first attacked the various pueblos in order to enslave the people and usurp the bottom lands for agricultural use. The blood flowed freely. The Spanish recreated the feudal culture of Spain in New Mexico with landed estates in the form of land grants given by the King of Spain.

These land grants featured the landed aristocrat on the choice land surrounded in the village area by the non-landed spanish and then in an outer area lived the "coyotes," mixed-race people and detribalized natives. They were the buffer against raiders. This "Rancho Grande" colonialist structure was based in agrarian pursuits and occupied the best bottom lands of the Southwest. The "Rancho Grande" of the colonialist cattle baron such as existed across northern Mexico and is fixated in the balance of the Latin American mentality, could not be established in the open spaces of New Mexico because the nomadic tribes could not be exterminated or subdued as were the sedentary pueblo people who were based mostly in the river bottoms. Centuries passed in New Mexico with the Spanish holding the fertile bottom lands and the nomadic tribes moving freely in the surrounding area. The tribes raided the Spanish and the Spanish in turn raided the tribes for slaves. Slaves were held in New Mexico society as well as being sent south into Mexico from the slave markets of Taos and Abiquiu. At the time of the Civil War, a Senate Investigating Committee found that New Mexicans held one-third of the Navajo tribe in forced slavery in their semi-feudal society.

The Chokonen, Chihinne and Bedonkohe bands first encountered Spanish near the watershed of the San Francisco river in Southwestern New Mexico in the Sixteen Hundreds. They came to work the mines in the Silver City area, south of the Mogollon Rim. The first groups of miners left, but later, others arrived for the silver metal. Like the personality pattern of other parts of the empire, swelling around the globe, the people invading the southwest carried the stamp of empire culture. These conquerors had light colored skins which they believed inherently superior, they were part of the flock of the Christian God, creator of the universe. They were part of a rising tide of machine makers and importantly they had the superior knowledge to "develop" the land and cultivate its ability to "produce."

They also came from a culture whose central value was material goods and they were being offered the prospect of land and the "resources" on it including the native slave labor. The magnetic dream that pulled them was akin to winning the status of the landed, aristocratic nobility of Europe, on the lottery. It was this Christian/imperial mind-set that helps explain the gigantic moral atrocities these people committed upon the "godless savages." The native people and the land were there to be plundered.

As we would guess, the first significant contact between Apaches and the Europeans in the area of the Watershed was tragic. The first significant event occurred at the mines at Santa Rita, between the Mimbres and Gila rivers. Mangas Coloradas (Red Sleeves) was chief of the Chihinnes. At that time the Governor of the Mexican state of Chihuahua was offering money for Apache scalps. A man named Johnson and a number of his friends invited Mangas Coloradas and his band, reported to be several hundred, in to the mining camp for a feast. When the Apaches had begun the feast, the miners opened up on them with either a gatling gun or cannons (reports conflict). A large number were killed. Mangas Coloradas was wounded, but he escaped, carrying only his son Mangus who had not been killed.

Later, in mid-Eighteen Hundreds, when the Americans had taken the Southwest from Mexico, a Colonel Carleton came out of California leading a group called the California Column who were going to fight in the U.S. Civil War, in the east. By the time these men reached Arizona and New Mexico it appeared that their services would not be needed as the war had ended but ambitious to make a name for themselves, they began to attack Apaches. At about this time Mangas Coloradas went into the camp of these Americans to attempt to make peace with the new kind of Europeans. As he was there under a flag of truce, nonetheless he was killed. His head was then cut off and boiled. Later the skull appeared on the east coast where it was exhibited to curious crowds in a touring carnival. Victorio then succeeded as chief. In 1870 the Chihinne lead by Victorio were "given" a reservation at Ojo Caliente, west of the present Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, by Executive Order of the President of the United States. Shortly after this promise, they were forced out of that area and marched eighty miles west to Fort Tularosa on the San Francisco watershed and held over the winter by the military. The promised supplies did not arrive until spring and then they were of the characteristic inferior quality. Many died that winter of starvation and exposure. After this experience, the government allowed them to return to Ojo Caliente but shortly they were given orders to go to the death camp at San Carlos where hundreds of Apaches had already died of malaria and starvation with full knowledge of the United States government. Victorio and his group went there, some in chains, never again to have their promised reservation.

Members of the Chokonen, Chihinne and Bedonkohe bands several times broke out of the concentration camp at San Carlos. During the last escape of Victorio, many Chihinne and members of other bands went with him. From this escape they never returned. They were trapped by the Mexican Army at a range of mountains called Tres Castillos southeast of El Paso, across the border in Mexico. Almost all of the Chihinne and Bedonkohe, including Victorio, were killed at that time except for a few who escaped in the dark. During the last days of the Apache resistance, the Spanish had consolidated their hold on the bottom lands of the watershed and the Texas Cattle Barons were already swarming in. The invaders and their strident newspapers demanded that the last "renegade" Apaches either be killed or locked up on reservations. Nonetheless, several small groups stayed out and on the run for five long years as the press and the settlers remained in hysterics over the "savages". The main group was led by Geronimo and Nana of the Bedonkohes and Naiche, son of Cochise of the Chokonen. This small band of people who numbered less than 30 (25 men, the rest women and children) faced as high as 5,000 U.S. Army troops (one quarter of the U.S. Army at the time), scattered through the southwest, who rode grain fed horses and were securely supplied with food and other necessities from the U.S. Treasury. The Apaches had only their Pleistocene knowledge of the life of the area to sustain them, but because they were so pursued, they could not follow the seasons or even effectively hunt for the dwindling game of the area, yet, still they persisted by finding what they could on the land and by raiding the invaders.

Finally, the small band surrendered, September 3, 1886, to General of the U.S. Army, Nelson A. Miles who lied to the Apaches and promised them a reservation and much else that he could not deliver. The small band, who had been enticed away from their stronghold in the Sierra Madre of Mexico by General Miles’ lies, were led ultimately to the Southern Pacific railway tracks north of the border. There they were loaded into boxcars along with all of the Chokonen, Chihinne and Bedonkohe people that still survived on the San Carlos reservation. Based on the lies of the U.S. government, other leaders, Mangus, the son of Mangas Coloradas of the Bedonkohes and Chihuahua, leader of the northern division of the Chokonen tribe, both separately brought small bands in at that time. They too were loaded into boxcars.

This group of the last hold-outs and the remainder of those four tribes who were living peaceably on the Fort Apache and San Carlos reservations were all put on railroad trains and shipped to a military prison in Florida. More than 400 prisoners of the Chihinne, Bedonkohe, and the two tribes of Chokonen Apaches were confined as prisoners of war for 27 years. The duplicity was such that 14 Apache scouts who had turned on their own people and in fact were the only reason that the U.S. Army could get close to the holdouts, were also imprisoned. When the government in Washington, D.C. finally realized they had also imprisoned these 14 U.S. Army enlisted men (the Apache scouts) the government ordered them mustered out of the service and kept them imprisoned along with the others. Later, the remains of the tribes were confined at an army reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In 1913 an act of Congress allowed those who wished, to return to the Mescalero Reservation of New Mexico, but due to loud protests from the people of Arizona who now occupied part of the traditional home of the Apache, they were prohibited from moving to Arizona.

The Apaches were the human casualties of the march of Empire, and it was their resistance to invasion that is responsible for the Mogollon Rim country being even as relatively undamaged and uninhabited as it is, because they kept the settlers out and then when the Apaches were removed the cattlemen who had a sparse population moved in.

In 1913 some of the Apache men who had been young boys at General Miles "peace parley" when Geronimo surrendered, returned to their homeland to decide whether they wanted to come to the old original Chihinne "reservation" at Ojo Caliente or whether those returning would like to go to the Mescalero reservation in east-central New Mexico. Jason Betzinez describes the return to Ojo Caliente of the last handful of Chihinnes after many years of imprisonment and after the invasion of the cattle barons:

"In the morning we resumed our journey to Monticello. This was where the Apaches had made their first peace with the Mexicans. We did not stop, because we all were anxious to get on to our old reservation. From Monticello the route led up the dry creek bed which previously had been such a nice little stream. Now it was all filled in with gravel, which made it twenty jumps wide instead of the one jump which it had been before.

"We arrived at the old agency after dark but got up early next morning in our eagerness to look around at our old homeland. What a depressing sight it turned out to be! The whole country, once so fertile and green, was now entirely barren. Gravel had washed down, covering all the nice valleys and pastures, even filling up the Warm Springs, which had completely vanished. The reservation was entirely ruined. Looking around bitterly, I said to myself, ‘Oklahoma is good enough for me.’"16

There are now, no native people on the watershed, though there are many reservations within a one hundred-fifty mile radius, the White Mountain Apache, San Carlos, the large Navajo reservation in northeastern Arizona, Hopi, Zuñi, Ramah Navajo, Acoma, Laguna, Cañoncito, Alamo Navajo reservation near Magdalena, New Mexico and the Mescalero Apache reservation.17

The Ecological Effects of Colonization

Spanish herders began moving into the San Francisco watershed even before the Apaches had been eliminated. By the 1870's the wealthy Luna brothers of Los Lunas, New Mexico south of Albuquerque were grazing the area heavily with tens of thousands of head of sheep. At this same time, Spanish settlers were coming into the mountain valleys from the Los Lunas-Belen area bringing herds of cattle, sheep and goats. Some of the first were the Aragon family of the village of Aragon and the Benevidez family who settled near the present Village of Reserve. The first settlement, Plaza de San Francisco de Asisi del Medio was created near the confluence of the Negrito and San Francisco Rivers. Then the Jirón family came from Belen to establish Plaza Abajo, (Plaza San Francisco de Asisi de Abajo, or Lower Plaza). In the early days of Spanish settlement the relations with the Apaches were somewhat peaceable with only several Spanish people being killed (there is no historical record of how many Apaches may have been killed). The Chihinnes in the Ojo Caliente area had maintained cordial relations with the Spanish people of Monticello for many years, trading and visiting back and forth. The Spanish store at Monticello had sold guns and ammunition to the Apaches for years and that may have influenced the Apache perception of the Spanish people on the Rio San Francisco.

The Spanish headed for the most fertile lands in the area. They settled in the riparian life zone and by their occupancy extirpated most of the rich life of that area. The lush riparian zone rapidly gave way to the culture of empire as the beavers were killed out, the large ponderosas were cut for domestic use and the stock ate the willows and other vegetation. The riparian zone, except for a few areas almost inaccessible, was denuded and the rich soil that remained became pasture and agricultural fields. Much of this soil is now gone and much that does not have irrigation or seep water can hardly grow what the culture terms weeds. The sad remnants of the beaver tribe which in the past stretched down the San Francisco and then down the Gila to the Colorado river at Yuma, Arizona are now found only at two headwater tributaries of the San Francisco. There is a colony on Apache Creek and a strong colony at the top of the Watershed above Alpine, Arizona. The descendants of some of the beaver families try to branch out and establish new homes but persecution from the humans and the flood problems usually defeat them.

The only way that they can really re-establish themselves is to start from the top down. In that way they have some control of the water volume. If they try to build homes and environments in the lower elevations they are flooded out by the water coming off the overgrazed, undammed watershed above. As all of the flatter areas higher up are grazed by confined livestock, everything is eaten down to the low grass and there is nothing along the streams for the beavers to build dams with or to eat. Even in the higher areas the domesticated cow will tend to stay in the canyon bottoms and eat them out rather than forage the hillsides.

Throughout North America the extirpation of beavers has had a generally unmentioned and unrecognized but severe negative effect on the ecology. Beavers and their works are a main pillar of the life system. The dams of beavers affect the hydrology of entire life zones. This provides beaver marsh habitat in many areas of watersheds. It also helps insure live water in the streams year-around rather than the swift run-off. Beaver marshes create habitat for innumerable species, fish, frogs, insects and many others. Due to the micro-environment created, plant species are able to come into the area. Cattails and arrowleaf potatoes are types of small plants that are very useful for humans and animals. The trees that take root in these marshes, often willows, cottonwood and aspen, also lend their help in further enhancing the habitat.

Many species can be easily seen to engage in life activities that prepare and assist their environment for their benefit. With the beavers it is the creation of the marsh, that allows the water retention, that in turn encourages their preferred food trees to come in and live there. Never the less, the basic populations of Beavers were wiped out prior to 1900.

Following the Civil War at mid-century, a great push west occurred. Militarily freed-up from the civil conflict, the cavalry was turned on the native people. Military campaigns to confine or exterminate the native people served to "open-up the west." The prospect of super-profits had drawn the "mountain men" and businesses like the Hudson Bay Company west. At times as much as 1,000 % profit could be realized between what the traders gave the indians for beaver pelts and what they would bring on the New York and London markets.

When the Civil War closed, settlers rushed to grab the best of the free land. Mines and timbering were started where possible, but the quickest money came from cattle. As the Yakimas, the Nez Perce, the Paiutes, the Shoshones, the Blackfeet, the Cheyenne, the Navajo, Apache and many other tribes were confined, cattle swarmed onto their lands by the millions. With a herd of cattle and enough guns a cattle baron could move west onto free grazing land. The land of the American west was covered with good grass. In the Great Basin area there were the bunch grasses, in the Southwest there were the nutritious gramma grasses. With little investment other than a herd of cows and a crew who were handy with guns to scare off any settlers who might want to invade the range, a cattle baron could have a "cattle empire" for free. The herd would increase by the number of bred heifers each year and more western grass could be turned into yankee dollars.

Most of the herds that hit the Southwest and specifically the Watershed in this era came out of Texas. Rancher William French established a "spread" early on the Watershed before the Apaches were completely confined. He was the scion of an English colonial family whose children were spread from India to New Mexico as colonial administrators or "owners," and his comments on the invasion of Texans reflects his "social station:"

"During the years between 1882 and 1885 a number of cattle-men moved their herds, and occasionally their neighbors’ herds, from Texas to New Mexico. This migration was generally in the way of business, but sometimes its object was to avoid unpleasant consequences of a not too strict observance of the law. A new brand, a new name, and a new country covered a multitude of sins. Amongst those whose absence from Texas was tolerated only on the grounds of saving expense to the State were many cowboys who lost no opportunity of displaying their hatred of Mexicans. To them all Mexicans were ‘Greasers’ and unfit associates for the white man."18

The racism on which French comments is held by what is now the "Anglo" majority of the area, to this day. The Spanish hatred of Native Americans also continues.

The effect of the massive over-grazing of the West was first to extirpate much of the bunch grass and gramma from its usual habitat. Most of the other native grasses followed such that today it is rare to find an area anywhere in the West where there is a natural mix of native grass species like the original grass cover.

Not only did the grass suffer but the native wildlife declined. The cattle Barons continued massive campaigns of extermination, not just against the settlers and sheep herders but against the coyotes, wolves, mountain lions, grizzly bears, black bears, kangaroo rats, prairie dogs, snakes of all kinds, eagles, hawks, badgers, bison, pronghorn, wild mustangs and any other living thing that might by any stretch of the imagination threaten the life of or eat the food of- the sacred cow.

For example, prior to the 30-30 Remington repeating rifle of the cowboy and the "sod busters" of the plains, the herd of pronghorn in North America is estimated to have been 20 to 40 million. By 1908 only 17,000 remained. 19 The elimination of the beavers and over-grazing, especially of the riparian habitats, altered the hydrology of the continent. As the water run-off increased and flooding began, the narrow, shaded and slow flowing stream beds were torn out and became wide, dry washes filled with gravel and occasional "flash floods." As flooding increased, arroyo cutting began. The flood of water washes out the bottom of the stream bed in a lower elevation causing a small "waterfall" on its upper side. As flooding continues the small cliff face of the "Waterfall" successively crumbles away and the cliff face moves up the watershed. This causes the deep trenches that are termed "erosion canyons." As these canyons develop, what water there is, flows at a much lower level. What groundwater there was in the soil seeps out of the cliff faces on the sides of the erosion canyon thus dropping the water table for the whole area. Then much of the remaining plant life dies because their roots cannot reach water.

The life of the desert and semi-arid desert travels in many cycles. The cycles of the annual and perennial grass is such that it can survive drought - if it has been able to build up a sufficient sod layer in the good years. It is the storage of nutrient and life force in the elongating root system that allows the grass to revive its green parts after a fire or being eaten. When it must sacrifice the root to rebuild the green matter, the root shrivels correspondingly. If the green part of the plant is cropped down too often so that it cannot rebuild the root system, the plant will die. If there has been severe damage to it, then it will not be able to pull through the dry years.

There was a drought on the San Francisco watershed in 1892-1893 as there was in much of the West. It was so bad that many cattle died. Many natural animals no doubt also died. Another drought happened in the period 1900-1904.

A local historian tells of those days:

"In the early days, numbers and not quality counted and in the struggle for control, the range was seriously overgrazed until the 1892-1893 drought reduced numbers and permitted the range to recuperate somewhat. However, the range again stocked up.

"Another drought occurred in 1900 through 1904. A 1917 report stated, ‘But the range has never recovered from this past abuse and it seems as though this last drought had about finished it. When this reconnaissance was made, the range was practically denuded and there is yet no relief in sight!

"In 1927, D.A. Shoemaker made an inspection report of grazing on the forest and had this to say. ‘On the whole, the New Mexico division of this forest presents as poor a range management as I have observed on any National Forest area.’ "20

One of the functions of the vegetative life on the Watershed is to flatten out the water cycles. As in many semi-arid environments, the summer thunder showers are brief but heavy. One of the cycle harmonizers that have helped prevent this heavy onslaught of water and help it sink into the earth rather than run rapidly off, cutting erosion canyons, is the prairie dog. The burrows of the prairie dog absorb much water and this can be verified by watching them come top side during a thunder storm.

Another benefit of these small animals is indicated by the studies that show that the burrowing animals help the soil by the mixing of topsoil and mineralized subsoil into fine particles. The U.S. Biological Survey of 1908 came through, southeast of the Watershed, in Grant County. At that time they estimated 6,400,000 prairie dogs in that county alone. Now, there are no black tailed prairie dogs in that county adjoining the Watershed and a similar condition exists on the Watershed. They have been exterminated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife agency to placate the herders who felt their range was being eaten by these animals. Because the USF&W Service has killed untold millions of prairie dogs in the West, the black footed ferret which was their main predator is now thought to be extinct. These animals have not been seen in viable numbers anywhere for some years.

Part of the government subsidy to the public land grazers is the killing of rodents, coyotes, wild dogs, bears, bobcats and mountain lions. In 1981 Catron County which covers most of the Watershed, contributed $17,000 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for predator control. This was the county portion and the USF&W Service absorbed the balance. This money was spent to kill prairie dogs, kangaroo rats and coyotes. As there are 2,700 people in the county and one percent of the population are ranch owners and one third of these are absentee owners, according to Bureau of Land Management records, this represents a healthy subsidy to the herders and a significant destruction of life.

Many areas of the West, including the watershed, were formerly covered by vast prairies. As the grass cover was grazed out, many other plants came in, so that the nature of the area changed. The biggest factor in that change is that the grasslands no longer had enough vegetational cover to carry fire. Before the overgrazing, fires, whether caused by lightening or natives, burned swiftly across the top of the grasses. This helped maintain the grasslands. It removed dead debris for the growth of new green shoots and importantly burned off other competing vegetation such as the sage, juniper and piñon pine that the government now spends millions of dollars removing for the public lands ranchers, who are the people who have overgrazed the land so it cannot carry a fire.

Plants that spread when the annual and perennial grass has been killed out by overgrazing are sagebrush, creosote bush, tarbush, tumbleweed, rabbitbrush, colorado rubberweed, mesquite and various cactuses. These emergency troops attempt to cover the barren ground but usually are battled vigorously by the herders and their allies in government. These groups call the first aid crew, "invader plants." In their view it is the fault of the first aid crew for invading the range when in reality the cow herders cause it. Simply because one sees green on the land in semi-arid deserts does not mean it is in good health. The green may be the first aid crew.

Grass seeds ordinarily cannot germinate on bare ground. They need to be blown or float into some pocket of organic detritus that will shield them from the desiccating sun and hold enough moisture so that they can get a start. Providing this organic debris is an important role of the first aid crew which the government spends millions of dollars a year to kill. Although in some cases grass has difficulty growing directly beneath juniper trees, the shading on the periphery is another important role that these trees play in helping the grasses re-establish, because it slows the evaporation of moisture from the soil so that they can get a roothold. On the Watershed, the desert plants are moving north and higher up in elevation as aridity increases, they would move back down if the abused land were allowed to recover.

Not only has the riparian habitat suffered from the agriculturalists and grasslands because of the herders, but the miners have come also, although the heyday of mining is largely over. The frenzy of mining occurred on the Watershed basically in the area of the village of Mogollon from the late Eighteen Hundreds until early Nineteen Forties. In addition to polluting the waters from mining discharge, large amounts of local wood were needed to fire the smelters.

Local historian J.C. Richards tells of one among a number of mines in the area:

"Up Whitewater Creek four miles was the new gold processing mill town of White Creek or the Graham Mill, a 30 or 40 stamp type affair owned by the Helen Mining Company of Colorado. The town had a floating population from 100 to 200 people. The mill was using the mercury amalgamation system of gold recovery, using steam and pelton wheel water power. The steam boiler furnaces burned about fourteen cords of wood a day, so you can see why the hills are so barren of juniper trees."21

On the San Francisco watershed, fortunately, not the high volume metals such as iron or copper were smelted but only the more precious such as silver and gold. Even so the wood cutters and also the charcoal burners who cut for the commercial market, ranged over the high mountains and down lower, cutting the piñon-juniper and oaks. Their cutting damaged some areas so badly that it has not yet recovered.

Not only did the charcoal burners ravage the area but meat hunters ranged the mountains hauling out animals to sustain the food supply of the mining towns. This was a popular way to make a dollar when a person couldn’t find any gold and one old miner and meat hunter James A. McKenna tells of taking pack trains out and filling them up with turkey and deer. Mostly the gangs of meat hunters went out in the late fall and winter so that they could run the game into deep snow where they were helpless and then shoot as many of the herd as they could. He explains also that the miners wouldn’t buy the front portions of the deer- only the hindquarters. To McKenna’s credit he did jerk the non-salable part and then sold the jerky to the less wealthy Spanish people who had not only lost much family land but the whole U.S. Southwest to the newly arrived Americans.

Each group of meat hunters made many trips each year. A story McKenna tells of one trip gives an idea of the volume of animals hauled out of the forest in the Mogollon Rim country.

"The night before Nelson was to leave for Silver City, [to take a load in] we had on hand at least fifty turkeys. During the night we had a real break, for a flock of fifty or sixty more came to roost within three hundred yards of our camp. When they were settled in, light rain fell, which seemed to affect their flying. Opening fire, we dropped at least half of them. In the morning those that had fallen on the ground could not fly, and we got quite a few more by clubbing them as they ran by our camp."22

McKenna tells also of being in the vicinity of Elk Mountain on the northeast edge of the San Francisco watershed and seeing many wild horses and thousands of pronghorn feeding in the foothills, where a handful of pronghorn might be seen today and there is a complete absence of wild horses. McKenna, writing years later says:

"Looking back to fifty years, I have come to the conclusion I was using up more than my share of the natural resources which belong to all the people of the state, but you cannot put an old head on young shoulders, and at that time no laws had as yet been made to save the treasure of mountain and forest. But I never killed without good reason nor wasted the bounty of our southwestern mountains."23

Legend in New Mexico has it that the last Gila elk, another favorite animal of the meat hunters, died in a zoo in 1921. We do know that the last naturally occurring elk of the species Cervuc elaphus merriami died in 1909 and the race is now extinct. Those that exist on the Watershed now are Cervuc elaphus erxleben, transplanted from Colorado. These transplanted elk, although similar, are from a different ecosystem and give birth in May and June, unlike the former natural species. The fact that they give birth during the annual mini-drought is a definite problem for the transplants, but they are welcome given the circumstances.